I am fascinated by remote islands. Uninhabited. Which you can only reach if you have a boat. These Pacific islands exist. Far out in the Australian Coral Sea. Visited by birds, occasionally turtles. But it takes courage to sail there. Especially because I’m sailing alone. No one is out there to help you. And I know little about the dangers. Nothing should go wrong here. So, I start exercising.

Month: November 2024

Single-handed sailing – about the motivation and lessons of sailing without a crew

“Yacht” magazine published my article on sailing alone ‘And when do you sleep?’ in its 23/2024 issue. Here is the link to the German edition. Below you find an English translation.

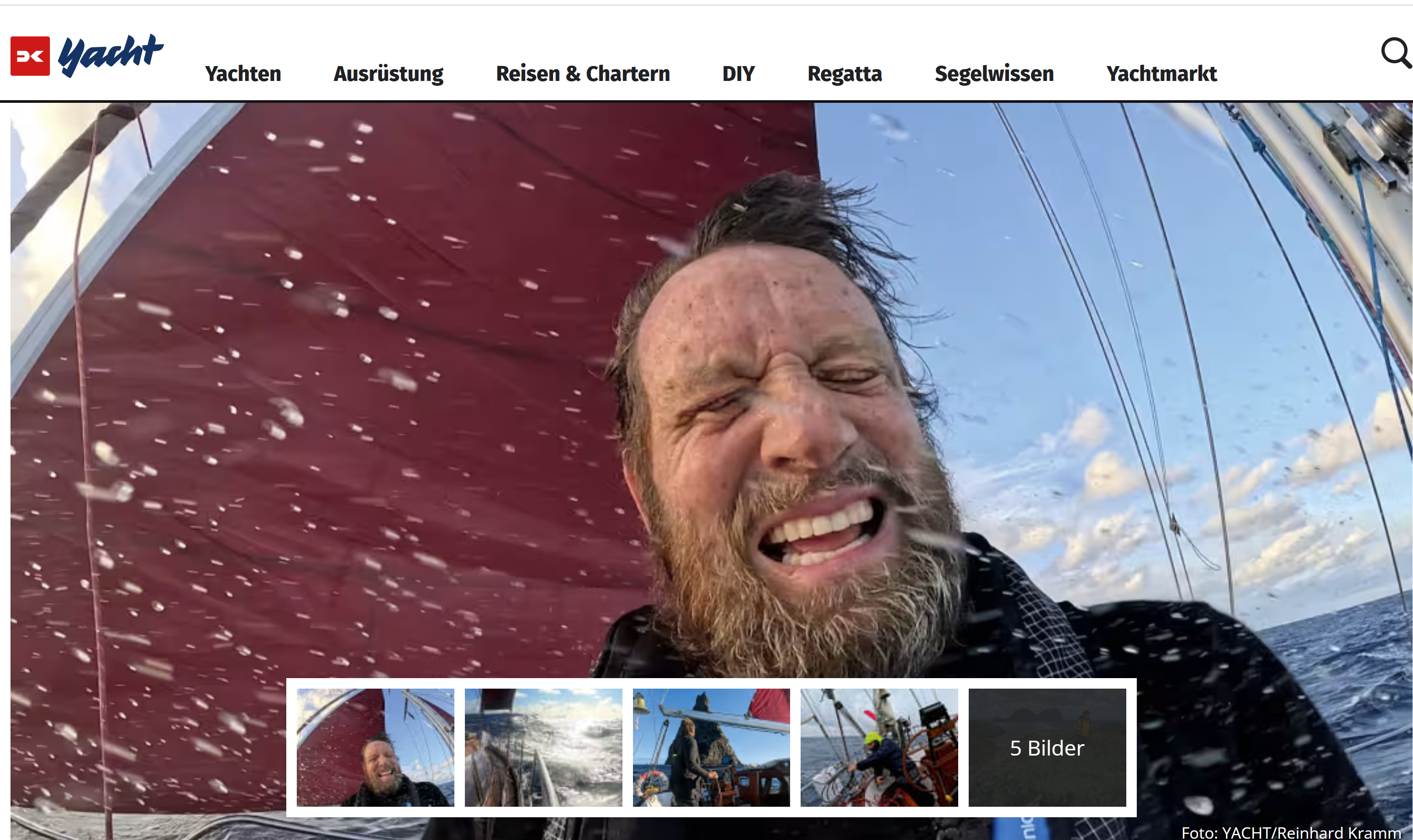

Our author, Swiss journalist Reinhard Kramm, has been sailing alone on the world’s oceans with his Motiva 39 ‘Reykja’ for almost five years. He talks about his experiences, his motivation to sail single-handed and the hard school of the high seas.

Sailing alone across the ocean provokes unpleasant questions. And rightly so. Sailing solo is dangerous. You can’t learn it on courses. There is only the hard way, making mistakes and learning from them. I’ve been at it for four years now and since then I’ve been rewarded with the best that sailing has to offer: Experiencing the limits and overcoming them.

Lord Howe Island in the Pacific. 500 miles east of Sydney. Yesterday a storm swept through the lagoon. After the gusts got faster than 50 knots, they took my wind generator apart. While I was still trying to figure out how to tame this wild piece of technology without losing my hand, the carbon fibres flew around my ears like 100 dollar bills. I have a replacement, I know how much they cost. The unpredictable ferocity of the gusts had overwhelmed the electric brake. And me too.

Mistakes happen all the time when sailing single-handed

The next day, the wind is blowing perfectly, 15 knots from the right direction. But the surf is high. ‘Do you want to go out in these conditions?’ asks the port operator, who is primarily a lagoon operator and monitors the narrow exit. I do. The surf breaks on the reef to the right and left. I estimate the waves at three metres and set course for the middle.

Right now I remember that I wanted to film with the GoPro camera. I leave the steering wheel alone and get it out of the saloon. ‘Reykja’, my ship, starts to dance up and down. A first breaker enters the centre cockpit and flows unerringly towards the saloon. Oh no. I forgot to close the companionway. I leave the steering wheel again and choke the windows into the holding in the wildly pitching ship. Done, and done with the exit too.

The sea outside is four metres high. Imposing, but not dangerous, it doesn’t break. Now unfurl the mainsail. It’s jammed. Now of all times. I don’t want to go on the foredeck, there’s a lot of wet spray and the deck is flapping like a chicken taking off. Should I have unfurled the mainsail at the anchorage as a test? I set the jib alone and switch off the engine. Sailing at last. And time to think about these mistakes, which can be particularly annoying when sailing alone.

I’ve been doing this for four years now. Having started in Fehmarn, I now have two oceans behind me. I haven’t gone overboard. I’ve never been seriously injured. Slightly yes, but more on that in a moment. But I’ve also never argued with myself, had to iron out other people’s mistakes, never eaten badly or had to do anything against my will. I am free and I am one hundred per cent responsible. Have I learnt from four years of mistakes? Some, I think, but by no means everything.

For the sake of systematics, I differentiate between passive and active safety. Passive safety is everything that I have gradually changed on the boat for single-handed sailing. Active safety is what I do differently today than in the past.

Building passive safety

An example of passive safety: ‘Reykja’ used to have a 63 cm high sea fence like many yachts. Pretty. Since Greece, she has had an 85 cm stainless steel railing. Bold. But a huge gain. I can walk onto the foredeck without the hassle of strapping myself to a safety line and then having to unbuckle it again at the stupidest moment, because the stretch rope isn’t long enough. I hold on tight. And I don’t put my life in danger if I step onto the foredeck and have to intervene.

My wish as a solo sailor was to be able to carry out all manoeuvres from the safety of the cockpit. In a position behind the steering wheel. I have to be able to steer, reef or close-hauled at the same time. It helps that ‘Reykja’ has a thirty-year-old furling system for the mainsail. I know you could argue endlessly about this topic. The fact is, I have to live with the furling system. Even in 30 knots of wind. And most of the time it doesn’t jam. In Lord Howe, only one halyard end got stuck in the spindle during the rocky exit.

The most important systems are now double, triple or quadruple. For steering: inside and outside helm, wind vane, autopilot, spare tiller, and not forgetting the design-related course stability of the long keeler. For power: wind and solar generator, portable generator, generator on the engine. Electronic nautical charts on plotters, tablet and smartphone. Sounds like overkill. Too much of a good thing. But even these systems quickly reach their limits. An example? ‘Reykja’ has two furling systems for headsails. On the forestay and on the cutter stay. Genoa and jib can replace each other, I thought reassuringly. Then, the day before yesterday, both systems failed. The genoa on the forestay jammed, no idea where.

I didn’t want to climb into the masthead, the waves were still going up. The jib, rolled out as a replacement, came from above four hours later. The shackle with which it is attached to the upper part of the furling system was broken. I had secured it with cable ties.

Six hours later, a strong wind would set in, 25 knots of true wind, gusting to 35, which is a lot on a close hauled course. The jib is too big to sail upwind at 35 knots without furling. But it is my engine, I can’t get anywhere with the mainsail alone. Fortunately, there was a small old jib somewhere in the depths of the boat. And I had a second, free cutter halyard. So my system was triply secured. And yet it was running low.

Redundancy is the magic word when sailing alone. The more systems that can replace each other, the better. For example, it would be unthinkable to steer 24 hours a day for several days. It is simply not possible. Also important: I have to be able to carry everything over the ship even in rough seas. With a genoa that weighs 30 kilograms, I reach my limits. Fortunately, in this case it was only the lighter jib.

Seeking active safety

What mistakes do I make myself? Perhaps I still haven’t fully realised that I am the most important object on board. Under no circumstances should I injure myself or fall out. Sailing alone means that I have to be okay. For example, I mustn’t get seasick. It usually takes me three days to grow sea legs, and I have to have medication that works. If I do get sick, I still have suppositories for vomiting in an emergency. I once made the mistake of not checking the expiry date. It was two years ago. The suppositories had liquefied in the meantime and it’s a tedious art to get them to work anyway …

Medication in general. You not only have to choose the right one, you also have to know its effect. When I had a bout of fever with vomiting, I opted for antibiotics. But I didn’t realise that they take up to four days to take effect. On the third day, I wanted to stop the treatment because I was still feeling lousy. On the fourth day, I suddenly rose from the dead.

It can also be less dramatic. I learnt not to sail the barefoot. The deck of ‘Reykja’ is a fakir board. Littered with traveller rails, blocks, lines and bollards. The result is two broken toes and various bruises. My compromise now is: never go on deck without sandals.

One last point: when do I sleep? The legal situation is clear: on a ship, a ‘proper’ lookout must be kept at all times (Collision Prevention Regulations, Rule 5). Technology can take over the lookout, but not always. AIS receivers and AIS transmitters with their alarm functions are the most important technology. In addition, VHF radio channel 16, three-colour lantern in the masthead due to high waves, radar, radar reflector and horn.

If I sail parallel to the coast, I only sleep as long as I would have if the wind shifted before crashing into the coast. Twelve miles parallel to the coast at six knots gives me a maximum of 90 minutes sleep, as the wind could pick up. If there are fishermen nearby, I don’t sleep at all. They have priority when fishing and sail bizarre, unpredictable courses. Otherwise, on the ocean: 90 minutes of sleep. That corresponds to one sleep cycle, with deep sleep and a dream phase. Or two sleep cycles if I haven’t seen a boat for days.

I know that some solo sailors set their alarm clock to 20 minutes. But I don’t have an organism that can keep that up for days or even weeks. My first rule: the lone sailor must be well, and this also applies here. A lack of sleep massively impairs your ability to react and make decisions. There must be opportunities to sleep for at least 90 minutes at a time.

And why single-handed sailing?

And why am I doing all this? Why am I sailing alone? That’s a philosophical question, not a technical one. Just this much: the single-handed sailor decides everything himself. The choice of course, whether to take more or less risk, what mistakes to make and how to correct them. There are no crew members to make mistakes, no partner to interfere, there are no excuses, there are no arguments, it’s just me. It’s a borderline experience.

But when I can sit at the bow for hours and look at the waves, when I don’t have to explain to anyone what I’m doing, when I can go back when I want, into the warmth of the saloon, check the course that is my course, correct my sail position without having to explain why – then I wouldn’t want to swap with anyone who is travelling in a crew.

Author Reinhard Kramm

The 69-year-old acquired the 30-year-old steel ketch ‘Reykja’ in 2017. After a total of three years of preparation, he set off from Fehmarn in 2020 at the beginning of the Corona period and has since explored the Mediterranean, the Caribbean and the South Seas.