Gale is part of the risk while sailing the world. Gale guarantees clicks on YouTube, surrounds the sailor with the aura of a hero. No wonder this word is used so often. But if you really get caught in a gale, it changes the ship and the sailor massively.

‘Sturm’ is wind with a speed of 41 – 47 knots (Seemannschaft. Handbuch für den Yachtsport, p. 578), or 9 Beaufort wind force. In English, a ‘storm’ is 48 – 55 knots, 10 Beaufort wind force. If a German-speaking person sails in a storm, the Anglo-Saxon person is still in a ‘gale’. So far, so unclear. English speakers are perhaps tougher?

But am I in a gale when isolated gusts reach 45 knots, or does it have to blow that strongly all the time? Am I talking about the true wind that the weather forecast indicates or the apparent wind that I experience on the boat? The differences here are immense.

Subjective is not objective

Let’s assume: The weather forecast shows 30 knots of wind. There is ‘steifer Wind’ or ‘moderate gale’, Beaufort 7.

Sailing against this wind, i.e. sailing high upwind, is almost impossible. The waves come sideways from the front, the bow crashes into them, REYKJA is stopped and picks up speed again. Spray splashes around my nose. The noise is deafening, water hits steel, the wind whistles around the masts. Because I’m sailing against the wind, the anemometer shows 35 knots of wind on board. ‘Stürmischer Wind’ or ‘gale’, Beaufort 8.

Now I turn the boat and sail with the wind. Suddenly it becomes calm. The waves come from behind, the boat picks up speed, sometimes at breakneck speed. Sailing is a pleasure. The anemometer shows 23 knots, ‘starker Wind’ or ‘strong breeze’, 6 Beaufort.

In both situations there is a true wind of 30 knots. Depending on the course, I experience two different worlds on the boat. What does the sailor or Youtuber who sails in the ‘gale’ refer to? Is he or she talking about the true wind in the weather forecast or the apparent wind on board?

And is he or she talking about the gusts? Because with 30 knots of wind according to the weather forecast, a gust can quickly blow at 40 or 45 knots. For a short time I’m in a Sturm, or strong gale, and then it’s steifer Wind again, moderate gale. Am I talking about the exception that makes me a hero, or the average, which is not worth mentioning?

Objectively difficult is subjectively bad

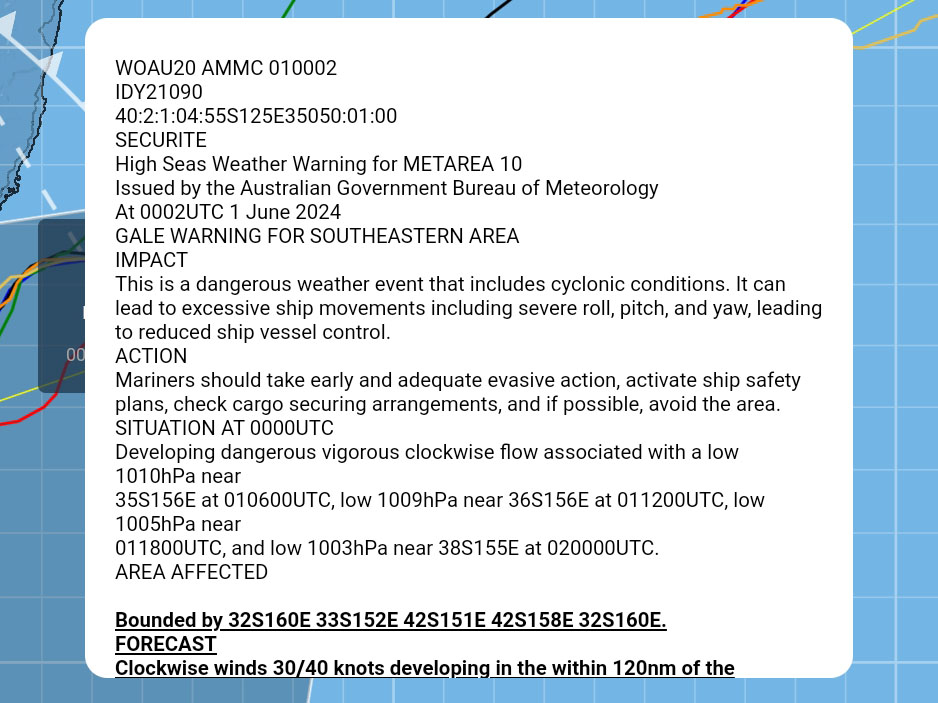

My course goes from Tasmania to Tonga. Strong winds are forecast for the south-eastern tip of Australia. The closer I get, the more threatening the weather forecast becomes. Finally, an impressive storm warning pops up on the tablet: ‘This is a dangerous weather event that includes cyclonic conditions’.

My reaction: denial.

It can’t be that this warning concerns me. There is a good wind, REYKJA is sailing fast. There is no sign of a storm.

Then it gets dark. The wind picks up, the waves build up into small hills. Fortunately, I can’t see them. But I can feel them. Of course I’ve fastened everything in the boat, as I do for every crossing. But then the washing-up liquid flies across the washing-up and into the bed. A door bangs. The scissors skid on the floor. Outside in the cockpit, the mast whistles, a sound I’ve never heard before. I have to hold on tight, I can’t stand at the wheel, only sit. I strap my lifejacket to the steering column.

A crashing noise. My gaze wanders over the ship. What’s broken? Finally I see it: the wind vane on the wind steering is missing. A gust of wind has simply blown it overboard.

Of course I had a plan. If there was too much wind or the waves were too high, I’d heave to, turn the boat crosswind, go into the saloon and pull the blanket over my head. And if even that became dangerous, there was the Jordan Drogue, the sea anchor, under the bunk. Unfortunately, I hadn’t installed it when there was less wind.

But I don’t have a replacement for the wind vane. Should I sail with the electric autopilot for the next three months? With its noise and power consumption? And what if it burns out?

I change my plan within seconds: Bye, bye Tonga – back to Australia.

Easier thought than done. The next bay I can call at in high waves is thirty nautical miles away, Jervis Bay. So it’s sailing now, 35 knots of true wind, 28 knots of apparent wind. Wind and waves diagonally from behind.

I don’t recognise my boat. REYKJA is bucking. Every time there’s a big wave, she tries to break course. The autopilot can’t steer in the opposite direction, protests with a shrill whistle and then plays dead. So I steer by hand. The jib bangs and flutters when I’m at right angles to the wind. I can’t imagine having to go on the foredeck now to put the spinnaker pole back. I try to manoeuvre my way round, but the course and jib position are at odds. It’s getting cold. I leave the steering wheel for just ten seconds to grab my long johns and Reykja is already lying across the wind and the jib is flapping loudly and menacingly.

After four hours, it’s done. The jib holds, as does the spinnaker pole. There’s a gaping hole in the sprayhood window and my head torch has disappeared. Even in the bay, the wind is blowing so strongly that REYKJA can only manage 2 knots under motor.

By the way: the true wind was probably just gale force wind, stürmischer Wind. In gusts it was Sturm, severe gale. There was never a ‘storm’. But I prefer German here, it makes me a hero.