Men in flowing caftans, women covered with shawls. Scarred, horrible wounds, beggars with hollow hands, black eyes and hair, running children, praying men on the jetty, the smell of decay and barbecue, buses on the opposite lane. Morocco is one sensory overload. For three weeks I dive into a parallel world to Europe’s boring predictability. Then I am full and flee, happy.

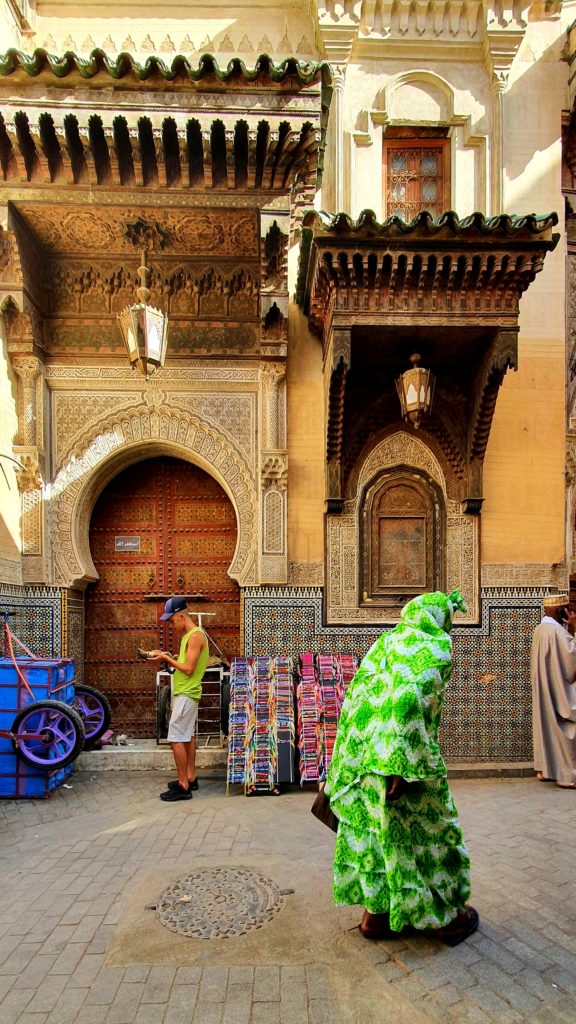

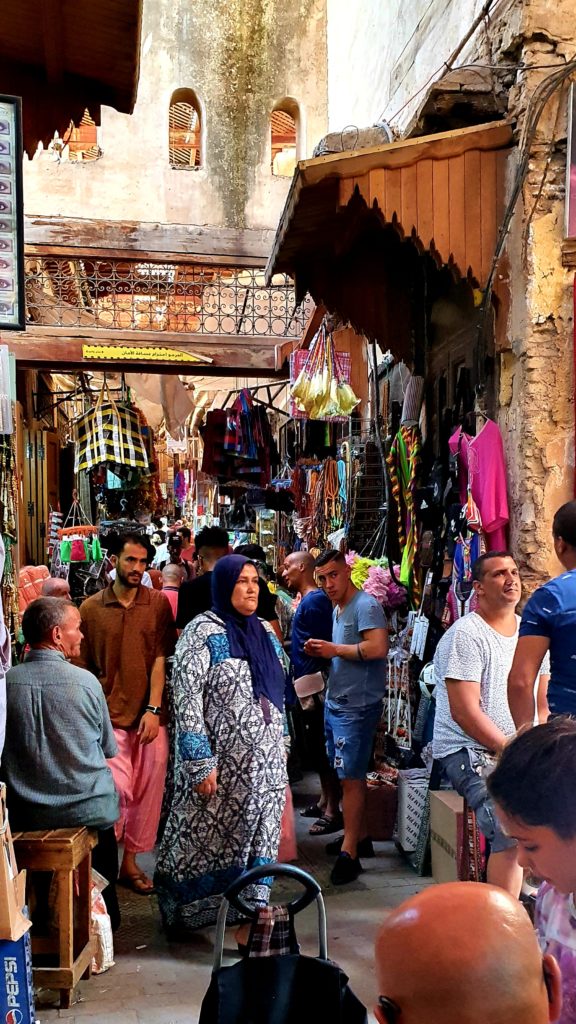

Actually, cities only interest me marginally. And then I land in Rabat and take the train to Fez. I don’t recognise myself. My carefully nurtured sociophobia vanishes into thin air, capitulates to the fascination of human complexity and emotions in the medinas: vendors sleeping on the counter, caves with table and chair whose meaning I cannot fathom, medieval tannery troughs, haggling, crowds, goods up to the ceiling, pointy Arab shoes in twenty shops in a row, blue and white caftans in entire streets. Everything vibrates, shouts and jostles. For days I let myself drift. I have long since lost my inner compass, only Google Maps keeps me on course. Finding an exit from the medina in Fez is an art.

Sahara in the summer

I rent a car and drive to the big landscapes. Not everyone has the glorious idea of wanting to hike in the Sahara in high summer. So I find myself quite alone in the Erg Chebbi with my backpack and hiking poles. In other words, I find myself alone as a hiker. Hordes of quads with Moroccan youths flit around my ears, successfully flattening every sand dune, no matter how aesthetic. The desert is just as much a backdrop for the pleasure society as the sea is for the hordes of jet skis, fast, loud and meaningless. Only when it gets dark am I alone in the desert.

Walking in the sand at over 40 degrees quickly exhausts my strength. My stomach is still fighting a diarrhoea virus from Fez. I am too weak to climb the ridiculous low 200-metre-high dune, even at night, under a full moon.

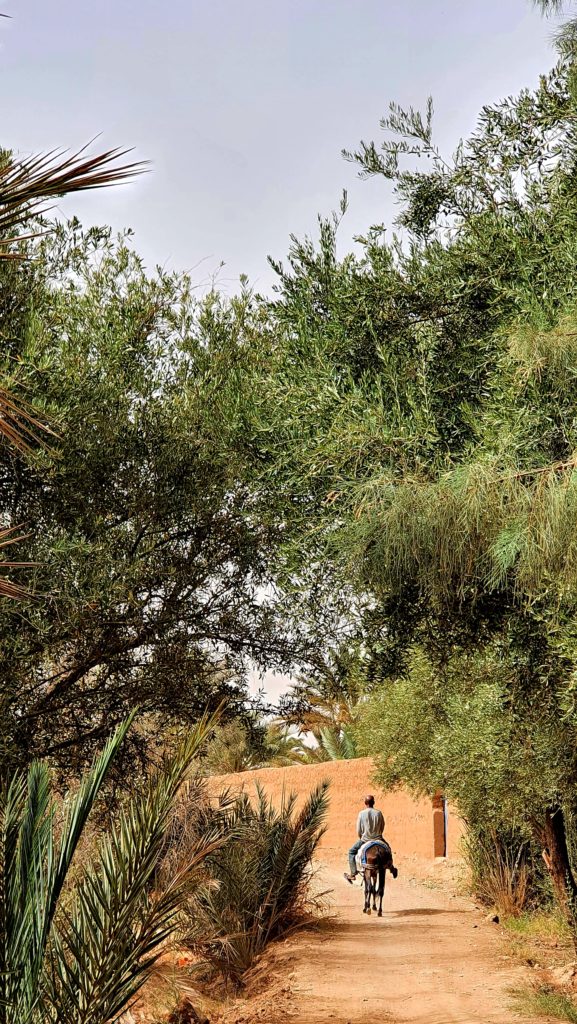

Palm trees in the sand

Instead, I discover the world of palm oases by car. Green valleys in the desert, with sophisticated irrigation systems, housing estates, kashbas made of clay, fields, fruits – and lots of shade. Despite internet research, I don’t quite realise how intact this world is. There are Cassandra calls in the media, water has long since stopped flowing in rivers, wells with diesel generators tap into the groundwater. There are palm groves that are yellow and withered. Others, however, look fat and green, the fields cultivated. The work is not hard, a farmer explains to me, cleaning a canal with a pickaxe in the blazing sun. The problem is the sale.

After some hesitation, I take hitchhikers with me. One breakdown on the blazing hot roads and I would be dependent on others. Hitchhikers depend on me. The police control stations outside the towns don’t like to see my passengers. They reach into the caftan pockets of a young Bedouin and warn me against him. I cannot judge how right they are. The Western Sahara with the Polisario Liberation Army is not far away. Another time, three officers with torches show up at my bivouac site at twelve o’clock at night and kindly but firmly invite me to continue sleeping in a field opposite the police station. “For my own safety,” they say.

Morocco’s great mountain and rocky deserts will be a paradise for hiking in winter. However, then I would probably no longer be the only traveller.